Soft.ware

Erica Whyte

Ruth Titus

Hope Elder

Mercedes Sharpe, Simay Ozturk, Nat Saavendra, Sizwe Inkingi, Hope Elder

Jeremy Glenn

R. Bolton, J. Glenn, V. Silins, U. Vira, J.Sanscartier, A. Alikpala

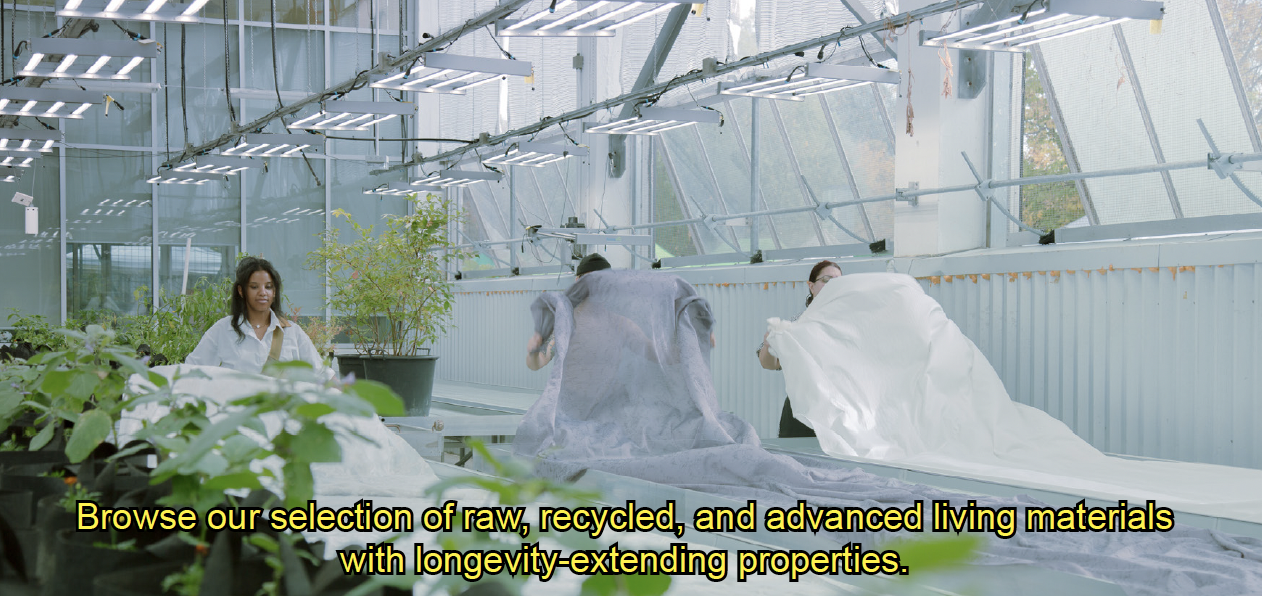

Soft.ware probes a potential future paradigm for how everyday things might be continually patched and recrafted — updated like software. The scenario imagines a culture of recycling and repair where literacies around materials science are more widely spread and people are incentivized to make their textiles and devices last longer.

Overview

In industrial design and material sciences, as in the textile and apparel industries, considerable research and innovation efforts go into developing sustainable new means of manufacturing. Wasteful and environmentally damaging processes tied to legacy materials nonetheless remain destructive forces in the clothing industry.

Modern manufacturing has changed our relationship to materials, distancing people from the sources of the items they buy, own, and wear. How might we be nudged to take more responsibility for where our stuff comes from and where it goes once discarded? How will we care for and repair our everyday things?

On a grassroots level, people have always coordinated gifting networks, free stores, and swap meets to divert reusable goods from landfills. Flea markets and vintage shops can also facilitate more sustainable (re)use of material goods. DIY spaces and enterprises like Bike Pirates, Repair Café, and Free Geek Toronto are communities where people learn to repair and refurbish discarded items so they can be useful again. Such cultures of repair aim to extend the lifespan of things by fixing them rather than re-purchasing and replacing. Related activist movements like Right to Repair have also been effective in pushing for legislation. New York State's Digital Fair Repair Act which requires consumer electronics manufacturers to provide parts and repair manuals for their devices. Policies that protect product lifespans go back to the Care Labeling Acts of the 70s which continue to ensure consumers are informed on how to best care for their purchases, so that their stuff might endure the wear and tear of ordinary use.

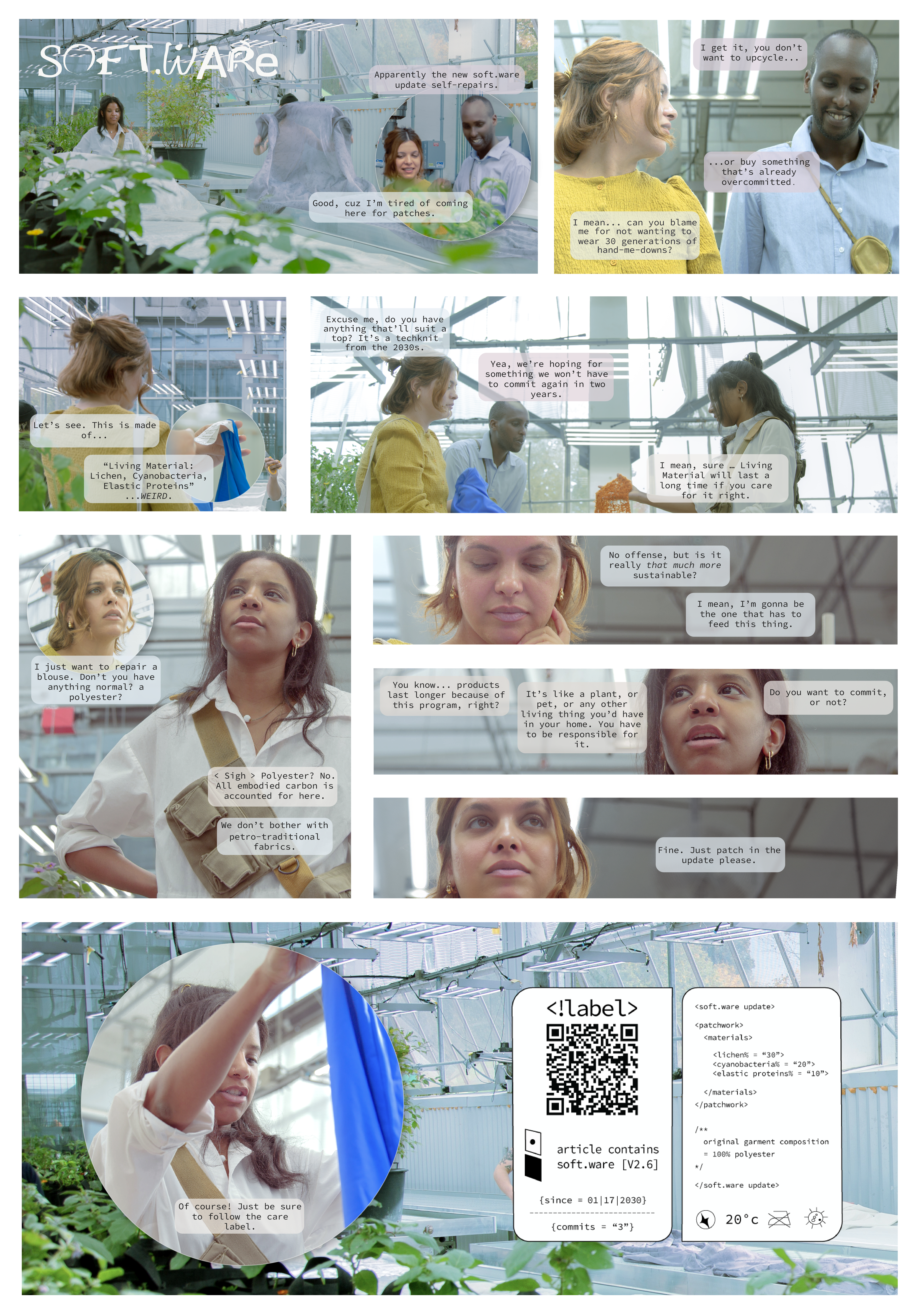

This project probes a potential future paradigm for how everyday things might be continually patched and recrafted — updated like software. It provokes questions about how a complex of issues — planned obsolescence, standardization, supply chain transparency, repairability, reuse, and upcycling, along with the introduction of emerging alternative materials — might restrict or empower our relationships to material culture. Set in a near future, the speculative photo-narrative depicts a community of people participating in a new kind of materials ecosystem — one that demands greater responsibility for the maintenance of a product over the course of its lifecycle. It hinges on a new care labeling standard that helps people mindfully navigate supply chains.

Narrative

This speculative photo-narrative illustrates a mundane encounter among people in a cooperative upcycling facility: two friends are looking to patch a torn and worn-out blouse. Though they're enthusiastic about the craft atmosphere of the community space, they're disappointed to find the traditional materials they loved have become outmoded.

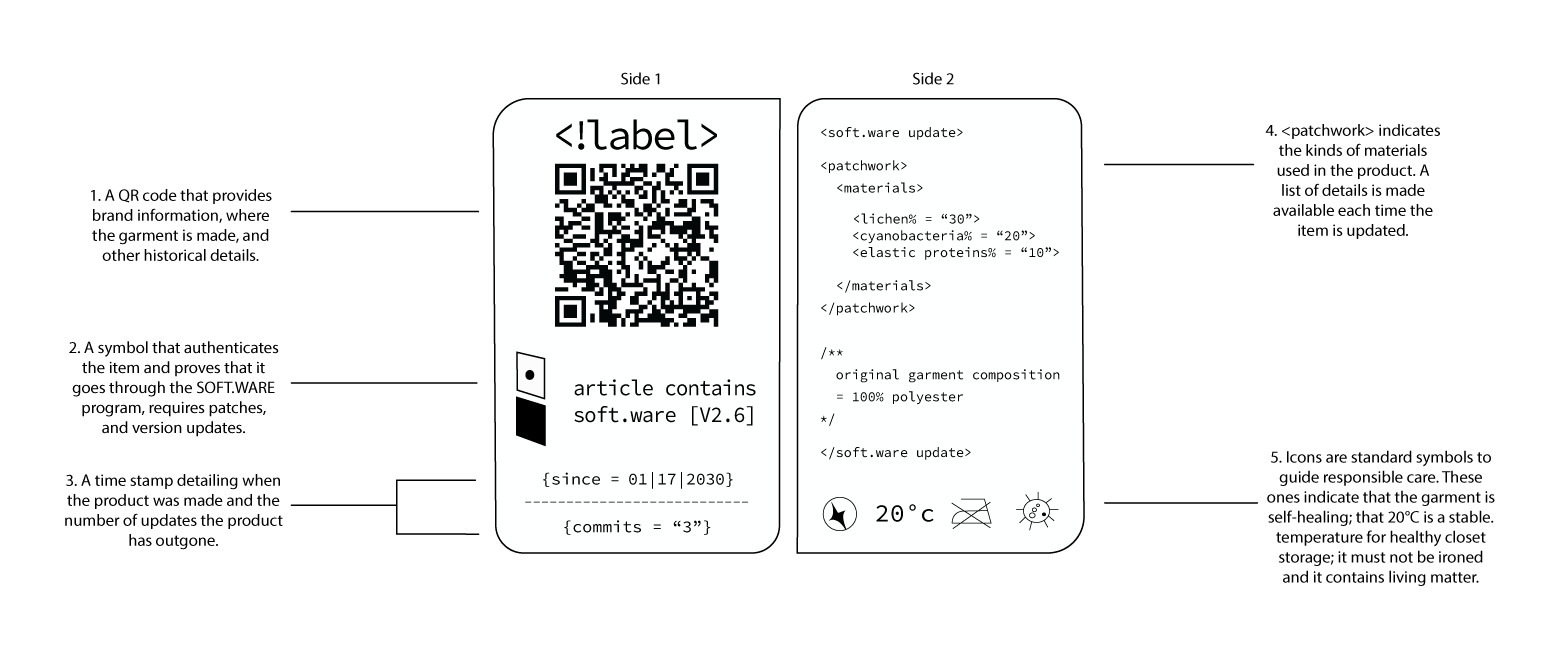

Artifacts

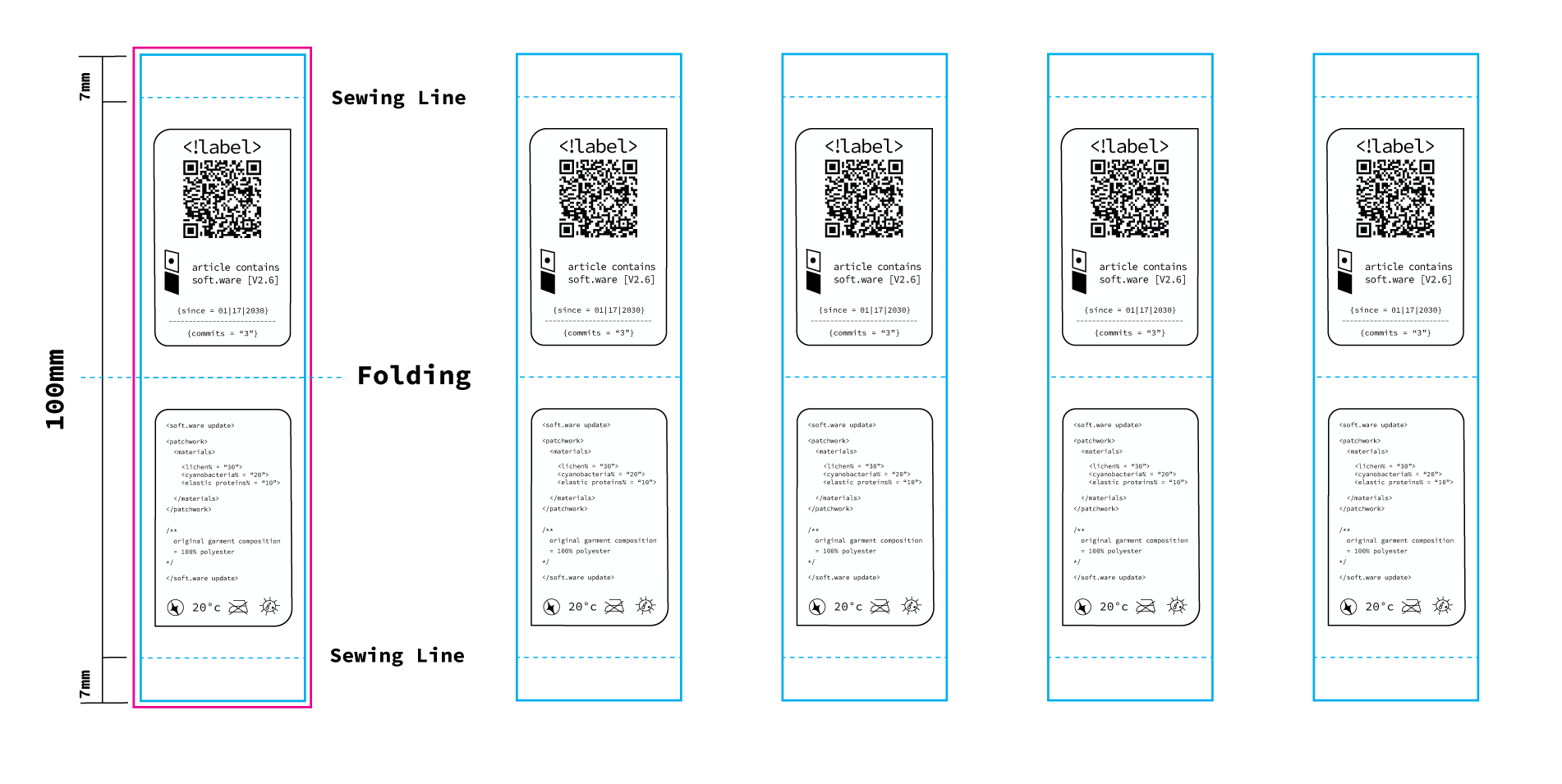

The material care labels attached to fabrics in this scenario demonstrate how designers and consumers could navigate supply chains, the upcycling of resources, and adoption of non-traditional material tech. The labels indicate industry-standard instructions for caring for a product over the course of its lifecycle. The idea is to de-incentivize fast fashion and petroleum-based fabrics while incentivizing people to mend and patch their apparel with regenerative materials.

Research

The Jacquard Loom, with its binary coded punch cards, is at least as celebrated for inspiring programmable computers as it is for revolutionizing textile manufacturing. How does the inherent interlacing of these two threads — software and textiles — suggest future patterns? What happens when we apply the language of software maintenance to the mending of our material world? Can software also be a lens that helps us understand and update large-scale industrial systems? To repeat the process, threading weft through warp, we’re due to acknowledge our version history and wonder again how the traditions of weavers might repattern our modern operating systems.